Oxidative Phosphorylation

We're back at the arcade and still in the mitochondrion. We just can't get enough. This is our bonus game but also the most important round, because now we will convert our tokens from the citric acid cycle (NADH and FADH2) into tickets (ATP). This is where the bulk of ATP comes from in cellular respiration—not glycolysis nor the citric acid cycle, but oxidative phosphorylation.

If we break it down, it is not too hard to figure out what this long phrase means. "Oxidative" must have something to do with oxidation, which involves a transfer of electrons. "Phosphorylation" is a term we saw earlier, and it means adding phosphate groups. Putting them together, we must be talking about redox reactions and phosphate additions, which isn't all that different from what we dealt with in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle.

The main purpose of oxidative phosphorylation is to transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 and use them to power ATP production. Similarly, the main point of playing arcade games is to win tickets for prizes (okay, and maybe to have fun and earn high scores to impress our friends).

Oxidative phosphorylation happens in two steps: the electron transport chain and chemiosmosis. Let's take these steps one at a time and break 'em down.

All the ETC details we’re about to discuss are specific to cellular respiration and occur in mitochondria. There are other electron transport chains that function in chloroplasts and across the plasma membrane in prokaryotes, and while those are similar, they aren't what any of this is about.

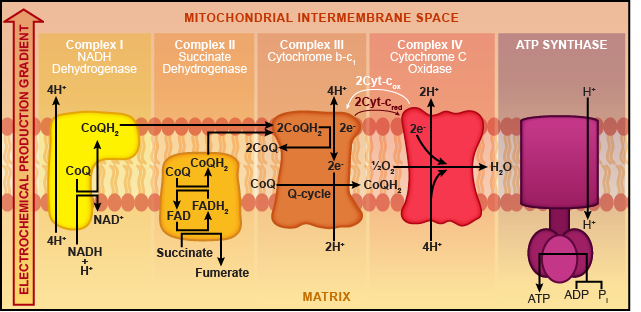

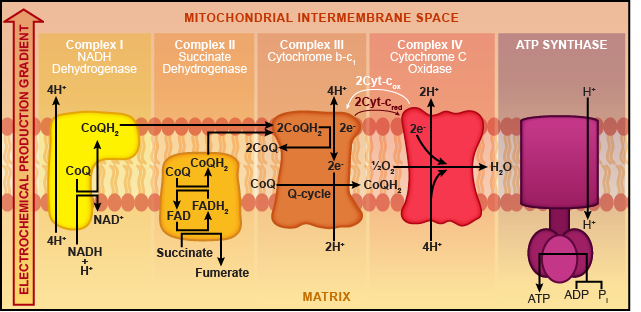

Embedded in the inner membrane of the mitochondria are protein complexes, which are basically blobs of protein. These blobs are numbered I, II, III, and IV (again with the creative naming). Some of the proteins are electron carriers and others are protein pumps. Recall that during the citric acid cycle, NADH and FADH2 were our outputs. These guys are just hanging out in the mitochondrial matrix waiting to load their tiny electrons onto the ETC.

Electrons jumping on the ETC result in NADH being oxidized. These electrons flow from one protein complex to the next in sequential blob order (I, II, III, and then IV). At the end of the ETC, a lonely oxygen atom is waiting patiently to be reduced. Electrons from protein complex IV team up with the oxygen and grab a couple of protons to make water (H2O). Oxygen is the last stop on this wild chain of events, and that's why we call it the terminal electron acceptor.

Protein complexes I and II are electron carriers, but complexes III and IV do double duty. Not only do they ferry electrons down the ETC, but they also function as proton pumps. Blob III uses the electron energy (aka electricity) to pump hydrogen ions (aka protons) through the membrane into the intermembrane space.

FADH2 wants in on the action, too, but NADH pretty much hogs the ETC for itself. That's because we generated a lot more NADH during the Krebs cycle (ten NADH compared to two FADH2). FADH2 has to get on at the second stop, protein complex II, but it follows the same steps afterward. Oxygen is still the terminal electron acceptor, and water is still produced. However, since far fewer FADH2 molecules are hanging out, there are fewer electrons getting on the chain; thus, less ATP can be made from FADH2. Sorry, dude.

While electrons ride the ETC, protons are pumped into the intermembrane space.

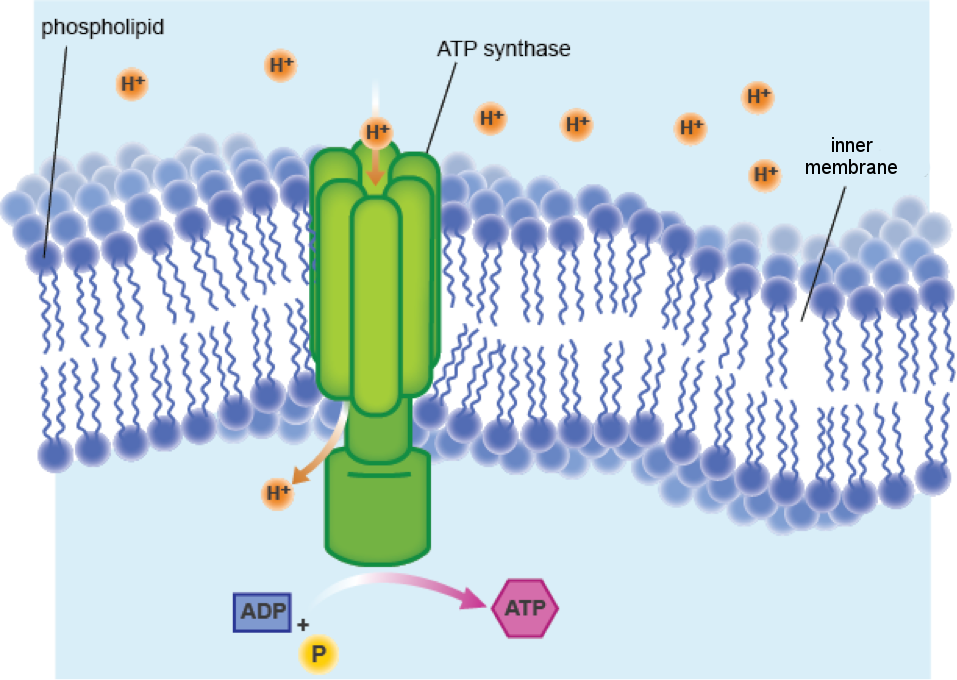

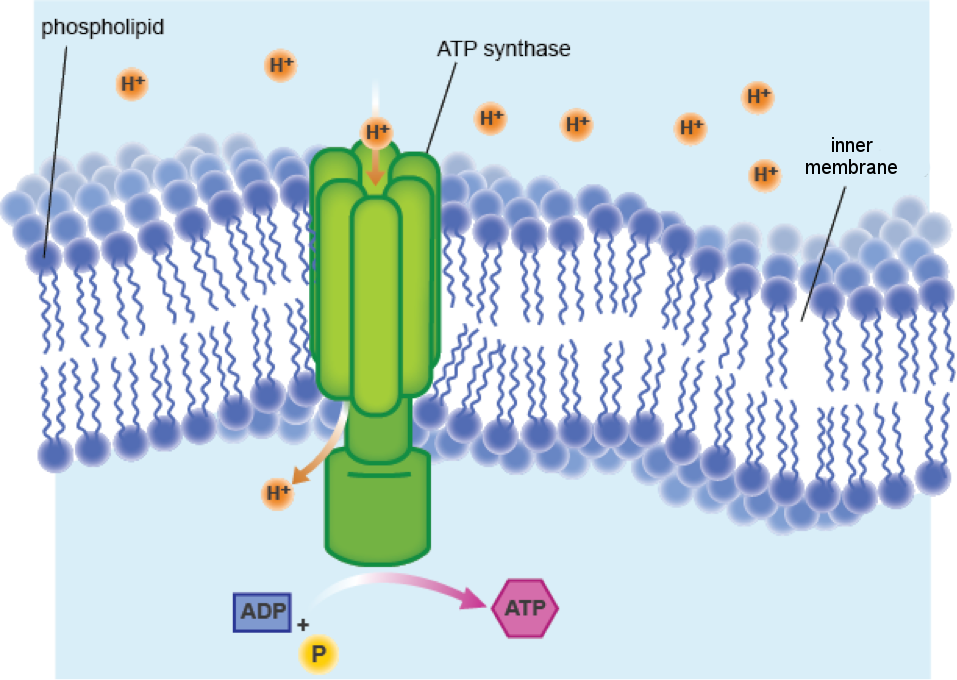

There are specialized channels in the membrane that the protons can flow through. These channels are formed by an enzyme called ATP synthase. And what does ATP synthase do? Make ATP, of course. The flow of protons through the ATP synthase channel and across the inner membrane is called chemiosmosis.

The word chemiosmosis is a mash up of "chemical" and "osmosis," and it's just a fancy way of saying ions move across a membrane. When water flows across a membrane, it's called osmosis, and chemiosmosis is a very similar process. In both cases, particles diffuse from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration. The gradient of high to low proton concentration has potential energy and can be used to power ATP synthase.

ATP synthase makes ATP by combining ADP and a phosphate group. Think of ATP synthase as a motor driven by protons. The steady stream of protons flowing through the channel provides the power to make ATP. In the same way that flowing water can move a water wheel, protons move the ATP synthase wheel.

Go, ATP synthase, go!

ATP synthase makes its own proton channel to get the protons needed for ATP synthesis.

Let's tally the score. From the citric acid cycle, we got ten molecules of NADH and two FADH2. The oxidation of one molecule of NADH during OP resulted in the formation of three ATP. That gives us 30 ATP. FADH2 oxidation resulted in two ATP (four in total). In this round of pinball, we won 34 tickets. Wow! High score! This means the process of oxidative phosphorylation produces 34 molecules of ATP per glucose molecule.

Thirty-four molecules of ATP…are we certain? Better slow your roll. Many sources will report a range for ATP generated during OP rather than a specific number. This is because the NADH produced during glycolysis is stuck out in the cytoplasm of the cell, while both the Krebs cycle and OP occur in the mitochondria. The mitochondrial membrane is impervious to NADH—that thing is on lockdown.

Sometimes NADH can hitch a ride and find its way into the mitochondria to be oxidized for ATP synthesis, and sometimes it misses the bus. Since each molecule of NADH is capable of producing three ATP molecules, if the two chaps from glycolysis aren't accounted for, then six fewer ATP molecules will be made.

Ideally, 34 ATP is the goal (and the number to remember for the test). However, despite the well-oiled machines these cells are, they aren't perfect.

Scientists have found that these mutations to the mitochondria often have an unintended side effect: the cell is unable to perform oxidative phosphorylation and produce those 34 ATP9. Without the energy power plant of OP, cancer cells have to rely on glycolysis alone to get their energy. Researchers are starting to focus on the mutations of mitochondria to find new treatments for cancer.

If we break it down, it is not too hard to figure out what this long phrase means. "Oxidative" must have something to do with oxidation, which involves a transfer of electrons. "Phosphorylation" is a term we saw earlier, and it means adding phosphate groups. Putting them together, we must be talking about redox reactions and phosphate additions, which isn't all that different from what we dealt with in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle.

The main purpose of oxidative phosphorylation is to transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 and use them to power ATP production. Similarly, the main point of playing arcade games is to win tickets for prizes (okay, and maybe to have fun and earn high scores to impress our friends).

Oxidative phosphorylation happens in two steps: the electron transport chain and chemiosmosis. Let's take these steps one at a time and break 'em down.

The ABCs of the ETC

We like to call the electron transport chain the ETC. It is sort of like the EAC (East Australian Current) in Finding Nemo, except the ETC transports electrons instead of fish and surfer sea turtles.All the ETC details we’re about to discuss are specific to cellular respiration and occur in mitochondria. There are other electron transport chains that function in chloroplasts and across the plasma membrane in prokaryotes, and while those are similar, they aren't what any of this is about.

Embedded in the inner membrane of the mitochondria are protein complexes, which are basically blobs of protein. These blobs are numbered I, II, III, and IV (again with the creative naming). Some of the proteins are electron carriers and others are protein pumps. Recall that during the citric acid cycle, NADH and FADH2 were our outputs. These guys are just hanging out in the mitochondrial matrix waiting to load their tiny electrons onto the ETC.

Electrons jumping on the ETC result in NADH being oxidized. These electrons flow from one protein complex to the next in sequential blob order (I, II, III, and then IV). At the end of the ETC, a lonely oxygen atom is waiting patiently to be reduced. Electrons from protein complex IV team up with the oxygen and grab a couple of protons to make water (H2O). Oxygen is the last stop on this wild chain of events, and that's why we call it the terminal electron acceptor.

Protein complexes I and II are electron carriers, but complexes III and IV do double duty. Not only do they ferry electrons down the ETC, but they also function as proton pumps. Blob III uses the electron energy (aka electricity) to pump hydrogen ions (aka protons) through the membrane into the intermembrane space.

FADH2 wants in on the action, too, but NADH pretty much hogs the ETC for itself. That's because we generated a lot more NADH during the Krebs cycle (ten NADH compared to two FADH2). FADH2 has to get on at the second stop, protein complex II, but it follows the same steps afterward. Oxygen is still the terminal electron acceptor, and water is still produced. However, since far fewer FADH2 molecules are hanging out, there are fewer electrons getting on the chain; thus, less ATP can be made from FADH2. Sorry, dude.

While electrons ride the ETC, protons are pumped into the intermembrane space.

Chemiosmosis and We're Done

Okay. Some electrons took a ride on the ETC. So what? The protein blobs pumping protons across the membrane have caused a bit of a kerfuffle. We've got a high concentration of protons outside the membrane, and we all know that the cells like to maintain balance. The protons are upset and want back through the membrane. But no dice. Proton pumps are a one-way street. They'll have to go around. Luckily, there's an alley.There are specialized channels in the membrane that the protons can flow through. These channels are formed by an enzyme called ATP synthase. And what does ATP synthase do? Make ATP, of course. The flow of protons through the ATP synthase channel and across the inner membrane is called chemiosmosis.

The word chemiosmosis is a mash up of "chemical" and "osmosis," and it's just a fancy way of saying ions move across a membrane. When water flows across a membrane, it's called osmosis, and chemiosmosis is a very similar process. In both cases, particles diffuse from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration. The gradient of high to low proton concentration has potential energy and can be used to power ATP synthase.

ATP synthase makes ATP by combining ADP and a phosphate group. Think of ATP synthase as a motor driven by protons. The steady stream of protons flowing through the channel provides the power to make ATP. In the same way that flowing water can move a water wheel, protons move the ATP synthase wheel.

Go, ATP synthase, go!

ATP synthase makes its own proton channel to get the protons needed for ATP synthesis.

Let's tally the score. From the citric acid cycle, we got ten molecules of NADH and two FADH2. The oxidation of one molecule of NADH during OP resulted in the formation of three ATP. That gives us 30 ATP. FADH2 oxidation resulted in two ATP (four in total). In this round of pinball, we won 34 tickets. Wow! High score! This means the process of oxidative phosphorylation produces 34 molecules of ATP per glucose molecule.

Thirty-four molecules of ATP…are we certain? Better slow your roll. Many sources will report a range for ATP generated during OP rather than a specific number. This is because the NADH produced during glycolysis is stuck out in the cytoplasm of the cell, while both the Krebs cycle and OP occur in the mitochondria. The mitochondrial membrane is impervious to NADH—that thing is on lockdown.

Sometimes NADH can hitch a ride and find its way into the mitochondria to be oxidized for ATP synthesis, and sometimes it misses the bus. Since each molecule of NADH is capable of producing three ATP molecules, if the two chaps from glycolysis aren't accounted for, then six fewer ATP molecules will be made.

Ideally, 34 ATP is the goal (and the number to remember for the test). However, despite the well-oiled machines these cells are, they aren't perfect.

Brain Snack

Cancer cells grow and cause tumors, in part, by mutating the mitochondria so the cells are resistant to apoptosis, or cell death. If cells don't die when they are meant to, they build up into masses of tissue, causing tumors.Scientists have found that these mutations to the mitochondria often have an unintended side effect: the cell is unable to perform oxidative phosphorylation and produce those 34 ATP9. Without the energy power plant of OP, cancer cells have to rely on glycolysis alone to get their energy. Researchers are starting to focus on the mutations of mitochondria to find new treatments for cancer.