Phages

Viruses that specifically infect bacteria and archaea (the other two domains of life) are called phages (either shortened for bacteriophage or archaeophage).

Phage comes from the Greek word for "devour." For example, "I am so hungry, I could phage an adult badger." Phages have been known for centuries to prevent bacterial disease. River waters shown to have curative powers against infectious diseases (such as the Indian Ganges and Yamuna rivers) are often rife with bacteriophages that kill pathogenic bacteria, as well as dirty laundry.

Types of phage morphologies

Phages come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, as seen in Figure 7, though they generally have an icosahedral or complex capsid structure. They can also be divided into two groups (big surprise, huh?):

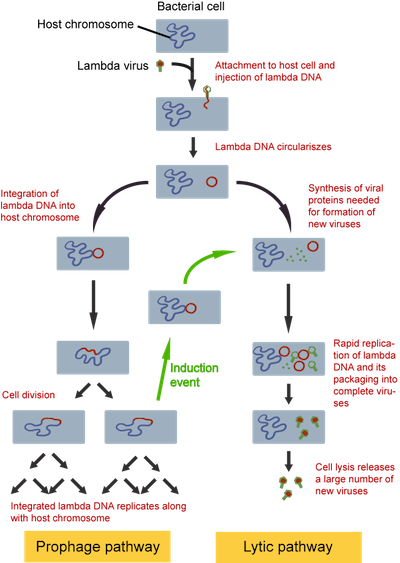

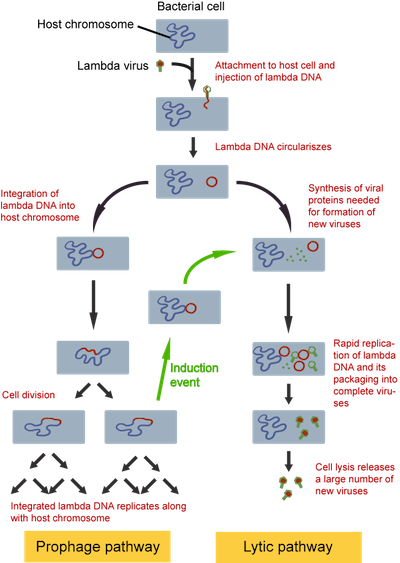

Temperate Phage Replication

Once the virus has integrated into the host DNA, it is referred to as a prophage, and is no longer invited to fancy virus dinners. These can be maintained in the genome of bacteria indefinitely, and often lead to pathogenicity of certain bacteria. For instance, the cholera toxin in cholera comes from the CTXφ phage, and the shiga toxin that was responsible for E. coli O157:H7 pathogenic bacteria that contaminated beef a few years ago and causes bloody diarrhea. Now try saying viruses are boring after you've pooped your insides, or what we like to call "Taco Tuesdays" at Shmoop.

Phage comes from the Greek word for "devour." For example, "I am so hungry, I could phage an adult badger." Phages have been known for centuries to prevent bacterial disease. River waters shown to have curative powers against infectious diseases (such as the Indian Ganges and Yamuna rivers) are often rife with bacteriophages that kill pathogenic bacteria, as well as dirty laundry.

Types of phage morphologies

Phages come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, as seen in Figure 7, though they generally have an icosahedral or complex capsid structure. They can also be divided into two groups (big surprise, huh?):

- Temperate (or lysogenic)

- Lytic

Temperate Phage Replication

Once the virus has integrated into the host DNA, it is referred to as a prophage, and is no longer invited to fancy virus dinners. These can be maintained in the genome of bacteria indefinitely, and often lead to pathogenicity of certain bacteria. For instance, the cholera toxin in cholera comes from the CTXφ phage, and the shiga toxin that was responsible for E. coli O157:H7 pathogenic bacteria that contaminated beef a few years ago and causes bloody diarrhea. Now try saying viruses are boring after you've pooped your insides, or what we like to call "Taco Tuesdays" at Shmoop.