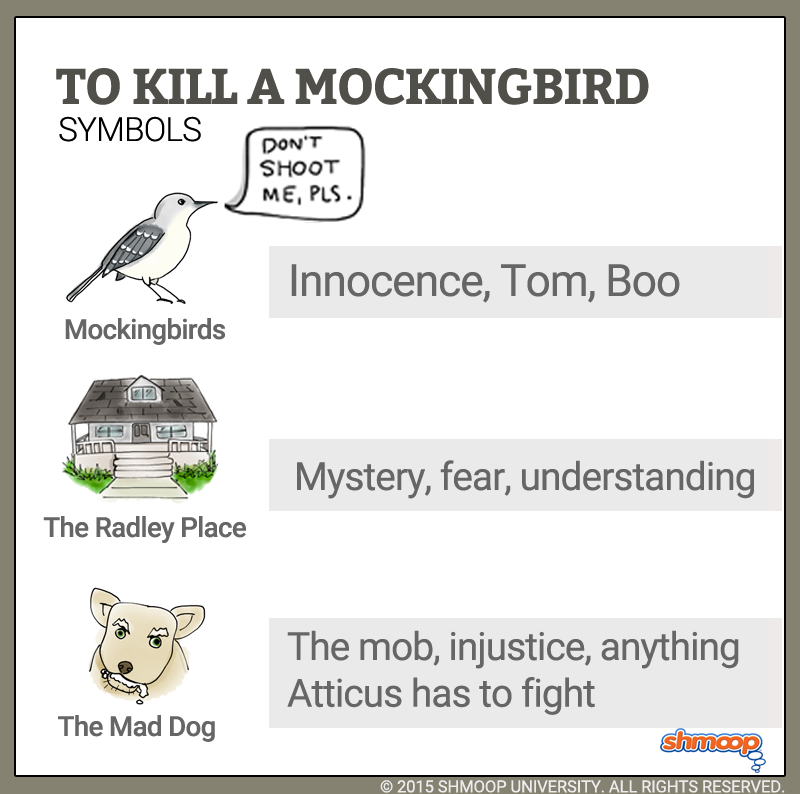

Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

If Maycomb were Disney World , the Radley Place would be the Haunted Mansion. And the Finch kids aren't the only ones who avoid it.

A Negro would not pass the Radley Place at night, he would cut across to the sidewalk opposite and whistle as he walked. The Maycomb school grounds adjoined the back of the Radley lot; from the Radley chickenyard tall pecan trees shook their fruit into the schoolyard, but the nuts lay untouched by the children: Radley pecans would kill you. A baseball hit into the Radley yard was a lost ball and no questions asked. (1.43)

Notice how all these statements have the quality of legends: the kids assume the pecans will kill them; the yard swallows balls; and even the African-Americans seem to have their own set of superstitions around it. It occupies a specific place in the community, a stand-in for all the fears of the unknown.

And most frightening is Boo Radley, the "malevolent phantom" (1.43). Scout isn't even sure he exists. And, like witches in Plymouth, the townspeople blame him for everything that goes wrong: "When people's azaleas froze in a cold snap, it was because he had breathed on them. Any stealthy small crimes committed in Maycomb were his work" (1.43).

Boo becomes a figure of superstition, a convenient excuse for bad things happening. Perhaps the house takes on such an evil reputation because Boo is never seen; when the kids look for him, all they ever see is the outside of the house, which becomes almost a stand-in for Boo himself. And like Boo, the house is isolated from its community:

The shutters and doors of the Radley house were closed on Sundays, another thing alien to Maycomb's ways: closed doors meant illness and cold weather only. Of all days Sunday was the day for formal afternoon visiting: ladies wore corsets, men wore coats, children wore shoes. But to climb the Radley front steps and call, "He-y," of a Sunday afternoon was something their neighbors never did. The Radley house had no screen doors. I once asked Atticus if it ever had any; Atticus said yes, but before I was born. (1.45)

The house ends up being a kind of black hole in the neighborhood, a house of mystery in the midst of the familiar. Maybe the Finch kids and Dill spend so much time trying to make sense of the Radley Place, and the Radleys, because they don't understand why anyone would voluntarily isolate themselves. If Maycomb is such a great place to live, why do the Radleys purposely keep themselves out of it? Is there something wrong with the Radleys, or something wrong with the community that they can't or won't be a part of? Why do they act so differently from everyone else?

On The Threshold

When Scout finally gets to the threshold of the Radley Place after Boo rescues her and her brother from Ewell, she does something weird. Instead of peering through the window to try to see inside the house that's intrigued the kids for so long, she turns around and looks outward. And she has a vision:

It was summertime, and two children scampered down the sidewalk toward a man approaching in the distance. The man waved, and the children raced each other to him.

It was still summertime, and the children came closer. A boy trudged down the sidewalk dragging a fishingpole behind him. A man stood waiting with his hands on his hips. Summertime, and his children played in the front yard with their friend, enacting a strange little drama of their own invention.

It was fall, and his children fought on the sidewalk in front of Mrs. Dubose's. The boy helped his sister to her feet, and they made their way home. Fall, and his children trotted to and fro around the corner, the day's woes and triumphs on their faces. They stopped at an oak tree, delighted, puzzled, apprehensive.

Winter, and his children shivered at the front gate, silhouetted against a blazing house. Winter, and a man walked into the street, dropped his glasses, and shot a dog.

Summer, and he watched his children's heart break. Autumn again, and Boo's children needed him.

Atticus was right. One time he said you never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them. Just standing on the Radley porch was enough. (31.25-31)

The Radley Place is like one-way glass: even though the kids couldn't see in, Boo could see out. And maybe he was just as interested in them as they were in him. Does this make Boo a part of the community after all? He may have watched what everyone else was doing like a spectator at a play, but he was able to break the fourth wall and step in when he was needed.

At the end of the novel, Boo disappears once more into the Radley Place, and Scout says that they never saw him again. But with her knowledge of what the world looks like from inside it, she'll now see the Radley Place as a living house instead of a dead one.