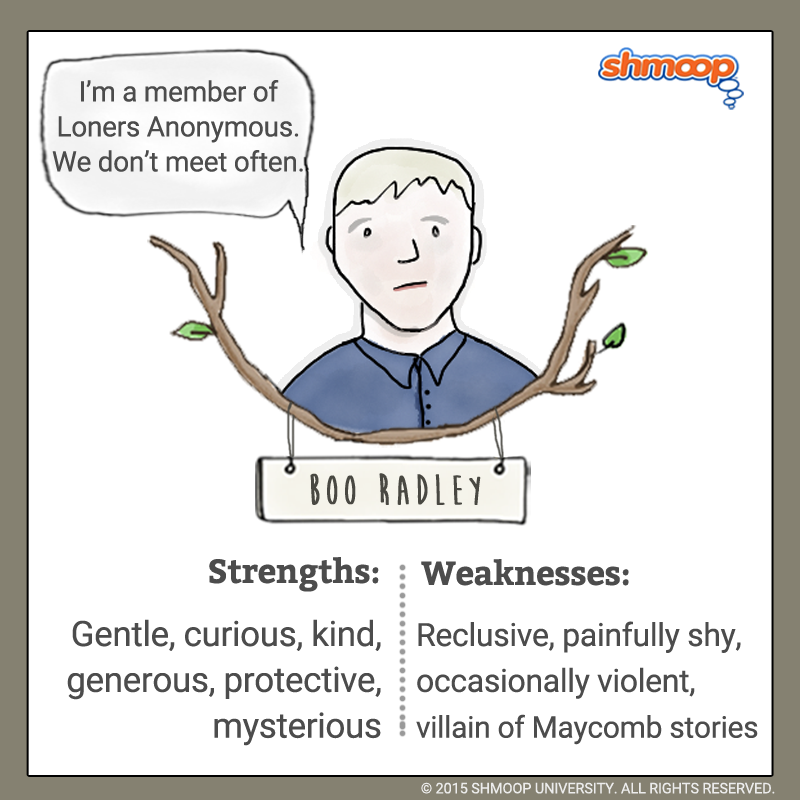

Character Analysis

Boo the Monster

If we take Jem's word for it, Boo is the kind of guy who, a century or so later, would probably be shooting homemade zombie movies on digital video in his backyard. And maybe taking it all a bit too seriously.

Jem gave a reasonable description of Boo: Boo was about six-and-a-half feet tall, judging from his tracks; he dined on raw squirrels and any cats he could catch, that's why his hands were bloodstained—if you ate an animal raw, you could never wash the blood off. There was a long jagged scar that ran across his face; what teeth he had were yellow and rotten; his eyes popped, and he drooled most of the time. (1.65)

Talking about Boo gives kids the same thrill as telling scary stories around a campfire. They've never seen him, so they (1) don't quite believe he is a real person, and (2) feel free to make up fantastic stories as someone else might do about Bigfoot. Their make-believe games, in which they act out scenes from his life, put him on the same level as the horror novels they shiver over. Fun!

Boo the Fantasy

But the kids aren't just afraid of him. There's also a strange longing for connection in the kids' obsession with him. Acting out of the life and times of Boo Radley could be a way of trying understand him by "trying on his skin," as Atticus always says. And they do try to say that they're really just concerned for his well-being:

Dill said, "We're askin' him real politely to come out sometimes, and tell us what he does in there—we said we wouldn't hurt him and we'd buy him an ice cream."

"You all've gone crazy, he'll kill us!"

Dill said, "It's my idea. I figure if he'd come out and sit a spell with us he might feel better."

"How do you know he don't feel good?"

"Well how'd you feel if you'd been shut up for a hundred years with nothin' but cats to eat?" (5.72-76)

The last line suggests that Dill at least feels some sympathy for Boo, and can imagine, or thinks he can imagine what he feels—and what he needs. It seems like Boo raises a really important question for the kids: can you still be human without being part of a community?

Boo the Reality

(Click the character infographic to download.)

After the Tom Robinson trial, Jem and Scout start to have a different understanding of Boo Radley.

"Scout, I think I'm beginning to understand something. I think I'm beginning to understand why Boo Radley's stayed shut up in the house all this time... it's because he wants to stay inside." (23.117)

Having seen a sample of the horrible things their fellow townspeople can do, choosing to stay out of the mess of humanity doesn't seem like such a strange choice. But it turns out only the ugly side of humanity can actually drag Boo out, when he sees Bob Ewell attacking the Finch kids.

While Tate insists that Ewell fell on his own knife, he also indirectly implies that Boo stabbed the man on purpose to defend the children. Since no one saw it (except, presumably, Boo), there's no way to know for certain. Rather than drag Boo into court, Tate decides to "let the dead bury their dead" (30.60). Weirdly, Tate seems less concerned about the negative consequences for Boo than the positive ones.

"Know what'd happen then? All the ladies in Maycomb includin' my wife'd be knocking on his door bringing angel food cakes. To my way of thinkin', Mr. Finch, taking the one man who's done you and this town a great service an' draggin' him with his shy ways into the limelight—to me, that's a sin. It's a sin and I'm not about to have it on my head. If it was any other man, it'd be different. But not this man, Mr. Finch." (30.62)

Angel food cakes! The horror! But for Boo, being the center of attention, even good attention, would be horrible. Even Scout, who's known the real Boo for less than an hour, gets it: "Well, it'd be sort of like shootin' a mockingbird, wouldn't it?" (30.68). Even the total-equality-under-the-law Atticus begins to think that sometimes a little inequality is what's really fair.

A New Perspective

When Scout walks Boo home, she's entering into territory she's seen all her life but never before set foot on. Turning to leave, she sees her familiar neighborhood from a new perspective—Boo's perspective.

To the left of the brown door was a long shuttered window. I walked to it, stood in front of it, and turned around. In daylight, I thought, you could see to the postoffice corner. […]

Fall, and his children trotted to and fro around the corner, the day's woes and triumphs on their faces. They stopped at an oak tree, delighted, puzzled, apprehensive.

Winter, and his children shivered at the front gate, silhouetted against a blazing house. […]

Summer, and he watched his children's heart break. Autumn again, and Boo's children needed him.

Atticus was right. One time he said you never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them. Just standing on the Radley porch was enough. (31.25-31)

A shift in perspective transforms Boo from an evil spirit into a guardian angel. What really cements it for Scout is an act of imagination, as she visualizes what the events of the last few years might have looked like to Boo. It seems like the book is telling us here that, to understand and sympathize with others, all you need is imagination. Maybe that's why Lee has a child tell the story—because children can use their imaginations. Sure, imagining Boo as a monster may not have been very nice, but it did make the kids try to figure out how Boo sees the world.

The book ends with a sleepy Scout retelling the story Atticus has just been reading to her.

"An' they chased him 'n' never could catch him 'cause they didn't know what he looked like, an' Atticus, when they finally saw him, why he hadn't done any of those things... Atticus, he was real nice...." His hands were under my chin, pulling up the cover, tucking it around me.

"Most people are, Scout, when you finally see them." (31.55)

Scout literally "finally sees" Boo, but perhaps there's more to "seeing" than that. The Tom Robinson case suggests that it's all too possible for people to look at someone and still not see that he's a human being just like them. Boo starts out a monster and ends up a man, but he never rejoins the Maycomb community. Or perhaps, in taking an active interest in the Finch children, he already has: perhaps his character suggests that the bonds that hold a community together can be more than just social ones.