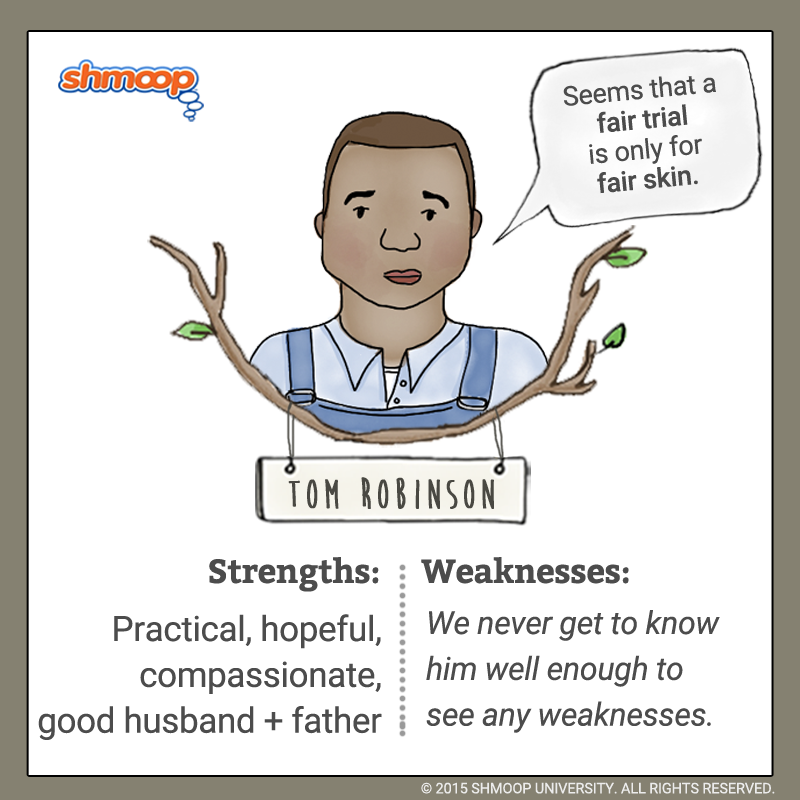

Character Analysis

Like Boo Radley, Tom Robinson isn't just an individual. He's also a litmus test for Maycomb's racism—and, unfortunately for him, it fails.

Before the Trial: Invisible Man

Tom Robinson's name comes up long before he appears in person, but the main issue setting tongues wagging isn't whether Tom is innocent or guilty, but Atticus's resolve to give him a good defense. Tom himself is basically absent from these debates, which assume either that he's guilty or that, regardless of his guilt or innocence, he should be punished for getting anywhere near Mayella.

And Tom stays invisible through most of the novel. When the lynch mob turns up at the jail where he's being held, they face off with Atticus while Tom himself listens silently from inside. It's not until after they leave that Tom's disembodied voice comes out of the darkness.

"Mr. Finch?"

A soft husky voice came from the darkness above: "They gone?"

Atticus stepped back and looked up. "They've gone," he said. "Get some sleep, Tom. They won't bother you any more." (15.128-130)

The conflict is between white people, with Tom as the unseen, powerless object they're fighting over. So why don't we see Tom until the day of the trial? The obvious answer is that we don't because Scout doesn't—but the novel could have brought Tom and Scout together at some point, so why didn't it? One answer is that if she had seen him, we wouldn't have the big reveal at the trial of Tom's disability, while doing things this way allows us to wonder along with the rest of the audience why Atticus is making such a big deal of Ewell's left-handedness.

But there might be more going on here: how real a person does Tom seem before we see him? And how sympathetic does he seem? Getting an idea of Tom only through what people say about him puts us as readers in a similar position to the people of Maycomb in terms of how much knowledge we have about him. It's up to us to make up our own minds about Tom—and about the people who judge him.

(Click the character infographic to download.)

At the Trial: Tom the Beast vs. Tom the Man

Even when Tom appears in person for the first time at the trial, everyone else gets to give their version of what happened before he has a chance to speak. At the trial, we get two versions of his relationship with Mayella, and they offer two very different stories: Mayella and her father tell the story that everyone expects to hear, about the Tom that is the town's nightmare. Tom tells the story that no one wants to hear, about the Tom that is himself.

The Ewells' Tom is a wicked beast who acts out of animalistic lust. There's no motivation for his sudden attack on Mayella—it's just assumed that any African-American man would rape any white woman, given the chance. (Atticus pokes some holes in this assumption in his closing remarks; see "Race" in "Quotes and Thoughts" for more.) The Ewells' Tom draws both on white fears of African-American men, especially where white women are concerned, and also on the stereotypes that justify white oppression of supposedly inferior African-Americans.

But Tom presents himself as a good guy who was just trying to help out a fellow human being in need. The only feelings he has for Mayella are compassion and pity, but it seems even those aren't acceptable either.

"You're a mighty good fellow, it seems—did all this for not one penny?"

"Yes, suh. I felt right sorry for her, she seemed to try more'n the rest of 'em-"

"You felt sorry for her, you felt sorry for her?" Mr. Gilmer seemed ready to rise to the ceiling.

The witness realized his mistake and shifted uncomfortably in the chair. But the damage was done. Below us, nobody liked Tom Robinson's answer. Mr. Gilmer paused a long time to let it sink in. (19.124-127)

Tom feels sorry for Mayella as one human being for another, but Mr. Gilmer and others can only see a black man feeling sorry for a white woman, suggesting the uncomfortable-for-them idea that white skin doesn't make a person automatically better off than anyone whose skin is black.

In his testimony, Tom presents himself as someone caught in an impossible situation: Mayella's behavior, as Atticus says, breaks the code of acceptable black-white relations, and so there's no right way for Tom to respond.

"Mr. Finch, I tried. I tried to 'thout bein' ugly to her. I didn't wanta be ugly, I didn't wanta push her or nothin'."[…]

Until my father explained it to me later, I did not understand the subtlety of Tom's predicament: he would not have dared strike a white woman under any circumstances and expect to live long, so he took the first opportunity to run—a sure sign of guilt. (19.76-77)

Tom does the best he can under the circumstances, but even his best isn't good enough. As a black man living in a white world, he's doomed from the start.

The Verdict: No Chance

Which story is the jury going to believe—the comfortable one about a black man raping a white woman, or a disturbing one about a black man pitying a white woman? Yeah. You know where this is going. But does the jury actually think Tom raped Mayella, or are they just afraid to say otherwise? Without a fly-on-the-wall narrator in the jury room, it's hard to tell.

We do know that the one jury member who was willing to acquit Tom was a relative of Mr. Cunningham, who was part of the mob that tried to lynch Tom. What made this unknown Cunningham's views on Tom different? He didn't have access to any additional evidence, but he did have a connection with someone who felt sympathy with the defense—perhaps that was enough to ignite a spark of bravery to go against accepted opinion and acquit Tom. Or perhaps he was inspired by Atticus's determined stand for what he believed in to do the same.

Aftermath: No Hope

After the guilty verdict that ignores Tom's own version of himself in favor of Maycomb's nightmare vision of him, Tom loses hope (and again disappears from the narrative). Atticus promises him an appeal, but who's to say the white men at the next level up will be any different than the fine citizens of Maycomb?

Tom's escape attempt seems crazy—running across a football-field sized prison yard to climb a fence in broad daylight with several armed guards watching—but perhaps that's the only way he saw of taking control of his fate. As Atticus says afterwards, "I guess Tom was tired of white men's chances and preferred to take his own" (24.71). Or perhaps Tom just couldn't take it any more and snapped, like Jem with Mrs. Dubose's camellia bushes.

In any case, Tom's death changes little about how Maycomb sees him, and in fact just reinforces their stereotypes further.

To Maycomb, Tom's death was typical. Typical of a n***** to cut and run. Typical of a n*****'s mentality to have no plan, no thought for the future, just run blind first chance he saw. Funny thing, Atticus Finch might've got him off scot free, but wait-? Hell no. You know how they are. Easy come, easy go. Just shows you, that Robinson boy was legally married, they say he kept himself clean, went to church and all that, but when it comes down to the line the veneer's mighty thin. N***** always comes out in 'em. (25.25)

Just like Tom's running away from the Ewell house gives most of Maycomb another excuse to believe in his guilt, his running away from prison once again gets worked into their pre-existing ideas about what African-Americans are like. No amount of white blood can overcome a drop of black blood in Maycomb genetics, and no amount of good behavior can save Tom from being dismissed as "typical."

What's more, it's not just Tom personally who is condemned for his faults, but the entire African-American race. That's one ugly way stereotypes work.

Dead Man Walking

While Atticus takes pride in getting Tom the fairest trial possible under the circumstances, and sees some hope in the fact that the jury took hours instead of minutes to reach the foregone conclusion of a guilty verdict, Mr. Underwood's postmortem newspaper editorial sees the whole trial as a sham.

"Atticus had used every tool available to free men to save Tom Robinson, but in the secret courts of men's hearts Atticus had no case. Tom was a dead man the minute Mayella Ewell opened her mouth and screamed." (25.28)

If it's true that in Tom's personal Choose-Your-Own-Adventure all paths lead to conviction, the question arises: what in Maycomb would have to change for Tom to have the chance of a different fate? What would have to change for him to be able to control that fate? And what does Tom's fate as it stands say about Maycomb as a community?